Vital fluids

You never know what you’ll turn out to have in common with your co-workers; science writer John Arnst and I bonded over selling our blood plasma.

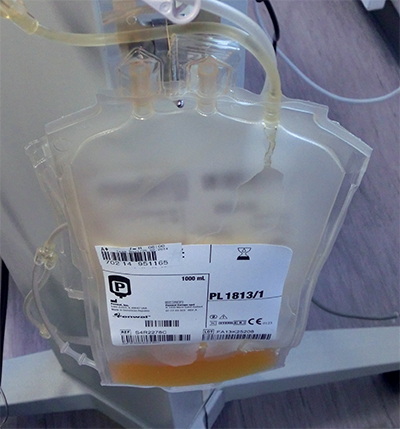

Plasma, the yellowish fluid in which blood cells and platelets are suspended, is essential for treating trauma patients and those with a number of other medical conditions. It’s needed in such large quantities that people get paid for it — though you aren’t technically being paid for the fluid; you’re being compensated for the hour or so that you spend lying in a padded lounge chair with a big needle stuck in one arm. A healthy person can donate about three cups of plasma twice a week. When I did it, my time was worth .

ANKAW脺/Wikimedia Commons

ANKAW脺/Wikimedia Commons

In that hour, a whirling machine separates the plasma from everything else in a process called apheresis and returns the blood cells and platelets to your arm. The machine is mostly clear plastic tubes and cylinders, so you can watch the process, which repeats about six times per donation, and monitor the slow drip of plasma into a plastic bottle. When it’s over, a pint of saline gets pushed into your arm to restore the fluid level.

Unlike blood donation, selling plasma is not an altruistic activity. It’s about the dollars on a debit card. John said he did it for about six weeks right after he graduated from college. I was an underpaid newspaper editor and single mom when I sold my plasma off and on for about a year, long enough for my arms to develop some suspicious marks and for my iron levels to dip perilously a couple of times.

While reclining in that lounge chair, I thought a fair amount about the marketing of bodily fluids, so when John mentioned Stephen Withers’ efforts to turn other blood types into O and its possible impact on the blood donation industry, all my old questions came back: Why do people get paid to donate plasma but not blood? If people give their blood for free, why does it cost so much when you get a transfusion? How do blood banks persuade enough people with the right types of blood to donate?

I was not the first person to think about this. Just Google “selling blood” and numerous on the topic pop up.

John writes that the blood industry is in trouble. Can it be saved by science? We don’t have an answer to that question, but our February feature story certainly lays out the issues and explains how blood (both industry and science) got where it is today. It’s a good read.

Enjoy reading 91亚色传媒 Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from 91亚色传媒 Today

Enter your email address, and we鈥檒l send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Opinions

Opinions highlights or most popular articles

Survival tools for a neurodivergent brain in academia

Working in academia is hard, and being neurodivergent makes it harder. Here are a few tools that may help, from a Ph.D. student with ADHD.

Hidden strengths of an autistic scientist

Navigating the world of scientific research as an autistic scientist comes with unique challenges 鈥攎icroaggressions, communication hurdles and the constant pressure to conform to social norms, postbaccalaureate student Taylor Stolberg writes.

Black excellence in biotech: Shaping the future of an industry

This Black History Month, we highlight the impact of DEI initiatives, trailblazing scientists and industry leaders working to create a more inclusive and scientific community. Discover how you can be part of the movement.

Attend 91亚色传媒鈥檚 career and education fair

Attending the 91亚色传媒 career and education fair is a great way to explore new opportunities, make valuable connections and gain insights into potential career paths.

Benefits of attending a large scientific conference

Researchers have a lot of choices when it comes to conferences and symposia. A large conference like the 91亚色传媒 Annual Meeting offers myriad opportunities, such as poster sessions, top research talks, social events, workshops, vendor booths and more.

When Batman meets Poison Ivy

Jessica Desamero had learned to love science communication by the time she was challenged to explain the role of DNA secondary structure in halting cancer cell growth to an 8th-grade level audience.