Women in science take on sexual harassment

"I was driven out of science by a harasser in the 1980s."

Coming from a woman who has since helped to found a scientific society, served as director of the Genetics Society of America and presented her research on sexual harassment to a 2018 National Academies panel, it is a surprising statement. But Sherry Marts left academia after finishing her Ph.D. at Duke and never went back.

2018 has been a banner year for confronting sexual harassment in science. The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine published on the high prevalence of harassment of women in science, and the National Institutes of Health and National Science Foundation are updating their sexual harassment policies. It appears that science might be catching up with the #MeToo movement, which has raised awareness of workplace sexual harassment. However, critics say that large institutions are moving too incrementally and could do much more.

Three decades ago, Marts said, she got almost no support from her institution. Her harasser was a technician in her graduate lab. She said he harassed her at work and then started following her home.

“I took it to the head of the laboratory, who told me to just deal with it,” she said. “I took it to the chair of the department, who said he didn’t want to hear about it. Then I thought, ‘If I take this to the dean, it’s going nowhere.’”

Instead, she made a report to the university’s Equal Employment Opportunity office. “The EEO office at Duke stepped in and made all of the faculty go through sexual harassment training again,” she said, “and basically called the chair of the department out on the carpet for not dealing with it.”

Sherry Marts

Sherry Marts

In the aftermath, Marts was not popular in her department. However, a faculty member offered her space to finish up her dissertation. “I found out later it was partly because he had a daughter doing a master’s degree in electrical engineering who was facing some of the same crap.”

Marts found a way to make the daily workplace harassment stop. But the solution cost her a place in her first graduate lab and her trust in the university.

And her harasser? “He stalked me for five years after he left. They let him resign; they didn’t fire him. And he’s now a faculty member at a university, in neuroscience.”

Parts of the scientific community have been trying to address sexual harassment for several years, motivated by high-profile cases that made headlines long before 2018.

Research into solving academia’s problem with sexual harassment and misconduct, comprehensively reviewed in a report by a panel that the National Academies convened (the same panel Marts presented her research to), has uncovered two broad themes that need to change: first, the way that institutions respond to and redress reports of sexual harassment; and second and more broadly, a culture permissive of sexual harassment in the first place.

Title IX investigations

Julie Libarkin, then an associate professor of earth and environmental sciences at Michigan State University, was assaulted by an emeritus colleague at a department social event. She reported it, but not until after she had been promoted to full professor. She has trouble articulating exact reasons for the delay but said that “for sure it was a combination of (post-traumatic stress disorder) and my department culture.”

Libarkin made a report to Michigan State’s Title IX office, which investigated the case. of 1964 states that no person may be discriminated against on the basis of sex in any federally funded training environment, so allegations of gender discrimination, sexual harassment or assault on campuses historically have been routed through institutions’ Title IX offices. (More on this later.)

Michelle Issadore is the senior associate executive director of the , a professional organization for the university staff members who hear and investigate sexual violence reports. Issadore noted that when speaking to targets of assault like Libarkin, these coordinators must walk a delicate line.

Julie Libarkin (left), Michelle Issadore (center), Jennifer Freyd (right)

Julie Libarkin (left), Michelle Issadore (center), Jennifer Freyd (right)

“The best Title IX coordinators I’ve worked with are really skilled at expressing their desire to support a student … within the constraints of the position,” Issadore said. “A Title IX coordinator who’s meant to be a neutral party can’t say, ‘I believe you. We’re gonna go after this person.’”

When a student or employee alleges an actionable violation, the Title IX office seeks to verify everything in the report. Stubborn neutrality can protect the rights of the accused and protect the institution from liability, but it also can do further harm to victims seeking redress for trauma.

Jennifer Freyd, a professor of psychology at the University of Oregon, presented her research on sexual harassment of graduate students to the panel that wrote the National Academies report. According to Freyd, “For many people, probably the majority of people, when they’ve reported sexual violence their life has just gotten worse.”

Research by Freyd and others suggests that the response to reporting sexual violence can be a strong predictor of how the target will fare moving forward, even stronger than the violence itself. For a person already recovering from an initial trauma, what Freyd terms “institutional betrayal” in the form of a skeptical or indifferent response from an institution the target depends on can be a second blow with disproportionate impact.

Libarkin noted that any institution will have a vested interest in protecting its public image and its senior, grant-earning employees and in avoiding a costly lawsuit. “Honestly, I don’t really feel like universities can adequately investigate power-based sexual misconduct. When there isn’t a finding of sexual misconduct, I’m not always confident that that’s actually accurate. There’s this potential for a university to brush it under the rug.”

More than a slap on the wrist

Even if the Title IX investigation confirms an initial report, the perpetrator may not face meaningful consequences. Sanctions are typically a matter for another institutional office, which Issadore says reduces the appearance of conflicts of interest.

Libarkin said her case was referred to the human resources department, which forwarded the report to her department chair. Though she had been promised anonymity, she said, the document included her name and some medical details. The department chair knew both her and the perpetrator as colleagues — a conflicted position that is not uncommon, according to Libarkin.

“I knew he wouldn’t know what I needed,” she said of her chair; she requested that a third party with more experience join the sanctioning process. She said she thinks this request was granted only because of her position as a full professor and because the perpetrator was retired.

After her chair sent the perpetrator a letter laying out the consequences of his actions, which Libarkin declined to describe, the man came to Libarkin’s house. “He showed up twice. I called the cops both times,” she said. “I don’t think anybody who hasn’t experienced PTSD can really understand how traumatizing it is to have this happen.”

In May, Libarkin posted on her blog that she had sent to the administration of Michigan State University. The memo details her objections to her experience with the university’s Title IX process, which she said was opaque, failed to maintain her anonymity and put her at unnecessary risk of retaliation. Libarkin gave MSU a number of specific policy recommendations to improve its Title IX process. She pointed out that because of institutional secrecy about investigations, she has no way of knowing whether her harasser victimized anyone else.

Cases like Libarkin’s show that filing a complaint through Title IX may do little to change harassers’ behavior. According to the National Academies’ report, compliance with Title IX is not enough, and institutions need to “move beyond legal compliance to address culture and climate.”

Federal interpretation of Title IX has been inconsistent. From 2011 to 2017, the Department of Education interpreted all campus sexual harassment and violence as subject to Title IX and investigated institutions accused of mishandling cases. Draft rules developed by Trump administration officials, leaked to the New York Times in late August, appear to tighten the definition of actionable harassment and prioritize due process protections for those accused of harassment or assault.

In August, National Institutes of health Director Francis S. Collins (right), shown with principal deputy director Lawrence Tabak at a December advisory committee meeting, received a letter from two members of Congress requesting that he take more serious action to prevent sexual harassment at institutions funded by NIH. NIH RECORD

In August, National Institutes of health Director Francis S. Collins (right), shown with principal deputy director Lawrence Tabak at a December advisory committee meeting, received a letter from two members of Congress requesting that he take more serious action to prevent sexual harassment at institutions funded by NIH. NIH RECORD

Federal agencies respond

In the wake of the National Academies report, federal science agencies have struggled to change how they address sexual misconduct. The National Science Foundation introduced and then partially backtracked from an aggressive new policy statement, while leaders of the NIH have resisted taking actions that would reach beyond its Bethesda, Maryland, campus.

At a congressional hearing in February on sexual harassment and misconduct in science, Rhonda Davis, head of the office of diversity and inclusion at the NSF, introduced a new reporting portal that allows scientists who are unsatisfied with their universities’ responses to file reports directly to the NSF. The agency can act as a neutral third party to address these sexual harassment claims.

In March, the NSF proposed updated guidelines to reduce sexual harassment in labs and at field sites it funds. Its would require grantees to report when an NSF-funded principal investigator has violated the agency’s code of conduct relating to sexual harassment and when a PI is placed on administrative leave related to a harassment finding or investigation. The initial proposal mentioned that the NSF can unilaterally revoke funding from investigators found guilty of sexual harassment.

Both the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation have struggled to redress sexual misconduct by the researchers they fund. The NSF (left) rolled out, then retreated from, a plan to cut funding to investigators who have committed misconduct. The NIH (right) has avoided such action altogether, arguing that discipline is universities’ responsibility. NSF building photo, NSF. NIH building photo, Lydia Polimeni/NIH

Both the National Institutes of Health and the National Science Foundation have struggled to redress sexual misconduct by the researchers they fund. The NSF (left) rolled out, then retreated from, a plan to cut funding to investigators who have committed misconduct. The NIH (right) has avoided such action altogether, arguing that discipline is universities’ responsibility. NSF building photo, NSF. NIH building photo, Lydia Polimeni/NIH

In response to the NSF’s request for public comment on proposed Article X, the 91—«…´¥´√Ω submitted several recommendations suggesting that the agency work with other federal entities, including the NIH, to create standard procedures for sexual harassment reports, ensure that investigators who transfer awards between institutions have no record of previous sexual harassment investigations and ensure transparency when responding to sexual harassment reports.

Tricia Serio

Tricia Serio

Tricia Serio of the 91—«…´¥´√Ω’s Public Affairs Advisory Committee crafted the 91—«…´¥´√Ω’s comments. She said she sees no provision in Article X for layers of response that calibrate to the wide spectrum of sexual misconduct. As a dean of students at the University of Massachusetts Amherst, Serio also sees difficulties not apparent to some advocates.

“The first institution to step forward is really sticking their neck out,” Serio said.

Institutions must comply with state-specific employee privacy laws, she said, one example of the delicate legal balance when pursuing meaningful changes to sexual harassment policy.

After collecting comments, the NSF hosted a roundtable in July to present a revised Article X incorporating feedback from the scientific community. According to 91—«…´¥´√Ω Science Policy Analyst Andr√© Porter, who attended, officials tempered the NSF’s initial plan.

“Officials emphasized the importance of due process and ensuring that all actions would be within their legal jurisdiction,” Porter said.

Instead of emphasizing unilateral action by the agency, he said, the new policy shows an agency “seeking instead to work with university administrations.” For example, he said, the revised article provides for ongoing support to trainees, even if a PI is removed from a grant; it does not prevent individuals from moving grants between institutions after a Title IX investigation unless university punishments like suspension have been applied; and it offers a standard operating procedure for grantee institutions to report such punishment.

Meanwhile, the NIH plans to change its procedure for investigating misconduct in labs on its campus. , presented at a meeting of the Advisory Committee to the Director, included a new provision that said that, instead of being handled internally by the head of each institute, all intramural allegations of sexual misconduct will be referred to a single office that will hire a third party to investigate. The agency has introduced new mechanisms for reporting and is putting the final touches on a campuswide survey of workplace climate planned for this fall.

Critics say these changes, while in line with the National Academies panel’s suggestions, are not enough. The NIH supports the bulk of the U.S. biomedical workforce, with more than 80 percent of the agency’s budget going to support university labs and nongovernmental research institutes. The NIH has resisted making bold policy changes to help curb sexual harassment in these labs. During the advisory committee meeting, Lawrence Tabak, principal deputy director of the NIH, said the agency funds institutions and not individuals. He said it is up to universities to ensure that their employees behave appropriately.

Lawrence Tabak

Lawrence Tabak

“These are university employees, and a university can deal with these matters as they see fit,” Tabak said later in an interview. “From the vantage point of a funding agency, our goal is to make sure that the work can be conducted in the most appropriate manner possible.”

In early August, U.S. Sen. Patty Murray, D-Wash., and U.S. Rep. Rosa DeLauro, D-Conn., ranking female members of the Senate and House committees that oversee the NIH, sent to NIH Director Francis Collins. They drew an unfavorable comparison between the NSF’s actions to redress harassment and those of the NIH, writing that the NIH “has largely failed to take steps to hold its awardee institutions accountable for fostering safe workplace environments.” They requested sweeping data on harassment trainings, the number and amount of legal settlements, and whether and how often the NIH audits grantee institutions, due back within just nine days of receiving the letter. Analysts said that the tight deadline was a way to indicate seriousness.

Murray and DeLauro are among the women leading the charge in Congress and in statehouses to fight sexual harassment. Melissa Melendez, California state assemblywoman representing the 67th district, has introduced a bill in the California statehouse to address sexual harassment in Sacramento. U.S. Reps. Barbara Comstock, R-Va., and Jackie Speier, D-Calif., have worked on multiple bills to prevent sexual harassment in and outside of Congress. Anne-Marie Boisseau, legislative correspondent for Speier, stated in a July email that a new version of H.R. 6161, a 2016 bill designed to address sexual discrimination in the workplace, is in the works. The updated bill specifically addresses sexual harassment in science.

Changing institutional culture: online activists

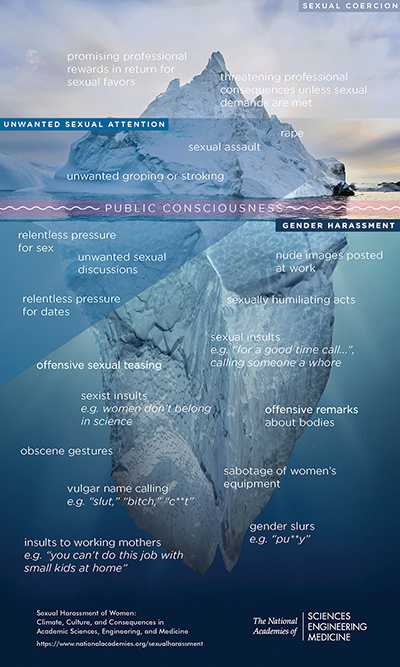

The National Academies report compares gender discrimination to an iceberg. Physical assault and coercion may attract more public attention, but such actions are borne up by less conspicuous sexual attention and gender harassment that often combine to create an environment permissive of more serious behavior. (click to enlarge) National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine

The National Academies report compares gender discrimination to an iceberg. Physical assault and coercion may attract more public attention, but such actions are borne up by less conspicuous sexual attention and gender harassment that often combine to create an environment permissive of more serious behavior. (click to enlarge) National Academies of Sciences, Engineering & Medicine

A hostile or sexist institutional climate is a strong predictor of sexual harassment, according to the National Academies report. Take, for example, the Salk Institute. In July 2017, three of its four female full professors filed suit against the institute, stating they had been prevented from applying for private funding available to their 27 male peers, denied opportunities to present their work and prevented from advancing. The institute denied the claims and harshly criticized the productivity and scientific caliber of the plaintiffs.

Less than a year later, the journal Science reported that Inder Verma, then the highest paid scientist at the Salk, had sexually assaulted numerous colleagues and trainees over decades. The Salk placed Verma, whose disparaging remarks about female colleagues were in one of the three discrimination suits, on administrative leave in April, and he resigned in June. Two of the suits have been settled out of court.

The complaints of pervasive gender discrimination targeting even the most well-established women in the institution were an indicator of an environment permissive of come-ons, harassment and assault, according to the National Academies report, which likened a culture of pervasive sexual harassment to an iceberg. Rape, coercion and assault, the forms of sexual violence that make headlines, are only the visible part of an iceberg buoyed by gender discrimination and unwanted sexual attention that rarely enter the public consciousness. If institutional leadership turns a blind eye to any form of sexual harassment, the report says, it encourages all harassment to persist. In the scientific hierarchy, “you’ve got power in the hands of a small number of people,” said Jennifer Freyd, the University of Oregon psychology professor. “If those people become abusers or tolerate abuse, that creates a very difficult situation for anybody who’s not at the top of that hierarchy because, if they say anything or do anything, they might lose their whole position in the system.”

The National Academies report focused on changing institutional cultures by preventing bad behavior rather than changing hearts and minds. The report includes a long list of evidence-based suggestions to change institutional climates.

The scandal that led to Verma’s resignation was a watershed moment for BethAnn McLaughlin, an assistant professor of neurology and pharmacology at Vanderbilt University Medical Center. In addition to his position of power at the Salk, Verma also had served as chief editor of Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, and he remains a member of the National Academy of Sciences.

BethAnn McLaughlin

BethAnn McLaughlin

To McLaughlin, the disconnect between the National Academies’ sexual harassment report and the science academy’s retention of members who have been found guilty of sexual assault, harassment and retaliation was unacceptable.

“It’s such a bad look for our most prestigious academies to have these predators … still in places of honor,” said McLaughlin, noting five other known serial harassers who have lost their jobs over their actions but still enjoy lifetime membership in the NAS. Her efforts intensified after reports alleged that NAS member Francisco Ayala, who resigned from the University of California−Irvine after a harassment finding, the ease with which a single NAS member can blackball nominees.

McLaughlin took to Twitter to speak out. In May, she started to remove confirmed harassers from the National Academies. By late July, more than 5,100 people had signed it. McLaughlin dismisses the objections initially raised by NAS President Marcia McNutt that the academies’ bylaws are difficult to change.

“Everyone says, ‘Gosh, it’s really hard to do this.’ It’s really not,” McLaughlin said. “All you have to do is, if you want an honor, submit a document from your institution that says, ‘I haven’t been found guilty of violating Title IX.’ That’s a really, really low bar.”

In in late May, McNutt and her counterparts at the academies of engineering and medicine stated that the three institutions “have begun a dialogue about the standards of professional conduct for membership in our three Academies.”

McLaughlin followed up with urging the American Association for the Advancement of Science to remove fellows who are sexual harassers. She has been vocal in criticizing individual leaders of both the NAS and the AAAS. Like many women who take a stand online, McLaughlin has faced significant pushback, some of it intensely personal.

Scott Barolo

Scott Barolo

To help her fight sexism, she has recruited male allies. It started with Scott Barolo, a Twitter friend she’s never met in person. “It’s tricky,” Barolo said. “You don’t want to be rushing in to try to rescue women on Twitter, because they don’t really need that.”

But McLaughlin says she told him, “We need all the heroes. Everybody in — let’s go.”

They made a list of male scientists on Twitter who support McLaughlin’s efforts and started #STEMTrollAlert. The hashtag is designed for women experiencing Twitter harassment or having the same argument over and over to “tag in” male allies to respond to arguments, sincere or otherwise, from men McLaughlin dubs trolls. “Instead of me having to explain it 700 times, their male peers have explained it,” she said.

Natalie Ahn

Natalie Ahn

“BethAnn has a gift for making it easy for other people to contribute,” said Barolo, a professor of cell and developmental biology at the University of Michigan School of Medicine. “She’s one of a number of women of science on Twitter who are articulating the sheer amount of work that women in science are expected to do … and changing norms. They’re changing cultural expectations about what’s OK in science.”

Natalie Ahn, immediate past president of the 91—«…´¥´√Ω and a professor of chemistry and biochemistry at the University of Colorado Boulder, acknowledges the risks of such activism. “I commend the individuals who are taking our institutions, funding agencies and scholarly academies to task on the issue of sexual harassment,” Ahn said. “Many are young investigators who have the most to lose by speaking out.”

Though public activism about harassment can come at a personal cost, petitions such as McLaughlin’s are a proven tool for changing scientific culture. Just ask the astronomers.

Changing institutional culture: scientific societies

The American Geophysical Union is regarded as a leader in tackling sexual harassment in science. In 2015, four women reported that University of California, Berkeley, astronomy professor Geoffrey Marcy, famous as an exoplanet hunter, had sexually harassed them. After a Title IX investigation confirmed their reports, the university said that it had put Marcy on notice, warning him to avoid misconduct in the future. When the allegations and his sanction became public, a petition to support his targets circulated throughout the earth and space sciences community. Marcy resigned shortly thereafter.

Scientific conferences are increasingly recognized as places where sexual harassment can occur. According to Sherry Marts, many serial harassers find targets at talks or poster sessions and begin by pretending an interest in their work. “The fact that it’s happening is ugly enough,” said Marts. “But the aftermath is that this young woman… is left thinking to herself, ‘I guess my research sucks.’” 91—«…´¥´√Ω

Scientific conferences are increasingly recognized as places where sexual harassment can occur. According to Sherry Marts, many serial harassers find targets at talks or poster sessions and begin by pretending an interest in their work. “The fact that it’s happening is ugly enough,” said Marts. “But the aftermath is that this young woman… is left thinking to herself, ‘I guess my research sucks.’” 91—«…´¥´√Ω

The AGU held a town hall about discrimination and bullying soon after . Personal stories shared at that event made it clear that the field had a problem.

“When we became aware of how serious the problem was, we felt an obligation to live up to our core values,” said AGU CEO Chris McEntee. “All of us, collectively, have to work on this problem.”

The AGU put together a task force to update its ethics codes and meeting protocols to promote a more positive work culture in the lab, in the field and in meetings. published in 2014 by anthropologist Kathryn Clancy had shown that a high proportion of women trainees were harassed by academic superiors in the field, and very few who had reported harassment were satisfied with the outcome of their reporting. Trainees in the earth sciences are especially likely to work in the field.

Sherry Marts, who left academic science for a career in nonprofits after her experience at Duke, helped the AGU to overhaul its meeting code of conduct. and consultant for professional organizations, Marts has worked on harassment at professional society meetings since about 2014. She ran a survey, loosely based on Clancy’s study, to gather information about harassment in meetings; 60 percent of respondents, who were overwhelmingly female, said they had been harassed at a meeting. Armed with data on the problem, Marts began working on systems to address it. She helps organizations to strengthen meeting codes of conduct and goes to meetings to act as a fact-finder and train society staffers in responding to harassment allegations.

According to the 91—«…´¥´√Ω’s Tricia Serio, a clear code of conduct is not just useful for catching offenders. It also changes culture. “It sends a really strong message to groups that have been targeted in the past that as a field we take this seriously.”

The AGU incorporated harassment into its definition of research misconduct and now employs a staff director whose sole job is to handle ethical matters in publication and professional conduct. Recipients of society honors and candidates for volunteer leadership are required to disclose any history of allegations or institutional investigations.

The National Academies panel cites the AGU’s work as a model for the role scientific societies can play in changing the culture. According to Frank Krause, chief operating officer of the AGU from 2011 to 2017, the society leads the field because its senior leadership recognized the importance of this issue and focused on doing something about it.

“That’s the key,” he said. “Not just accepting that ‘this problem’s bigger than us, let’s let somebody else take care of it.’”

Natalie Ahn of the 91—«…´¥´√Ω agrees. “The National Academies’ report clarifies the key role of institutions in sustaining — and changing — a climate that enables tolerance of sexual harassment,” she said. “It is up to all of us who hold power on a local level — all faculty members as well as administrators — to pay attention, actively work to enlighten our colleagues, and establish a clear code of conduct that is seriously enforced.”

A challenge that is poised to bedevil professional societies as it does universities is how to redress misconduct. “Everybody’s aligned with (the idea) that this is bad behavior,” said Krause, who is now the CEO of the Federation of American Societies for Experimental Biology, a coalition of scientific organizations that includes the 91—«…´¥´√Ω. “It’s really the publication of the issue and what the consequences were for a given individual that are so controversial to wrestle with.”

Because professional society members are not employees, said Marts, “there aren’t as many legal and liability constraints as there are in an employment harassment situation.”

For example, meetings are private events, so it isn’t difficult to ask problem attendees to leave. Other societies are discussing taking steps, as the AGU has, to revoke awards or membership in response to verified allegations. But should a university be informed of poor behavior by an employee at a conference?

“I like to say that’s a litmus test for how conservative your association’s legal counsel is,” Marts said.

The Experimental Biology meeting, which the 91—«…´¥´√Ω co-hosts with four other scientific societies, publishes a barring various types of gender discrimination and sexual harassment. Consequences now include removal from the meeting, being banned from future EB meetings or, in the case of egregious violations, a police report.

Thinking bigger: Women changing the culture

What unites the people driving the effort to stop sexual harassment and bullying in science is not their job titles. They aren’t all university presidents, deans, legislators or society executives. Instead, women in various positions of power are demanding change.

Marts believes that the National Academies report exists because a cadre of women and other minorities “have finally reached a level of power and success in science that they can actually afford to turn around and say, ‘This stops now.’”

Statistics cited by the National Academies report show that organizations that have more women in power are less likely to foster abuse. Promoting a more diverse and inclusive science workplace is a major goal of the National Academies’ report. But activists say there is a long way to go.

“We owe it to our younger colleagues and future leaders in science to create a wholly nondiscriminatory environment, where everyone can reach their full potential for creativity and discovery,” Ahn said.

In the weeks before the National Academies’ report launched, BethAnn McLaughlin, the neuroscience professor who started the NAS and AAAS petitions, teamed up with Michigan geophysicist Julie Libarkin to start where women can share their stories of harassment anonymously. One woman, who wrote under the pseudonym Jen, described an experience eerily similar to the one Sherry Marts had had in graduate school some three decades earlier. When Jen told her harasser to stop, speaking up cost her her PI’s goodwill and gained her very little, she wrote. According to Jen, the harasser is now a Howard Hughes Medical Institute investigator.

Hearing variations on the same few stories breaks her heart, McLaughlin said, but it also galvanizes her. She believes that after serial predators are removed from academia, the real work will begin: rehabilitating victims and making science a genuinely safe and welcoming environment for all. But for now, she said, she’s focused on the harassers.

“I got to the tipping point, where I was like, ‘Not one more generation of women. I will throw down as hard as I need to.’”

Daniel Pham contributed to this article.

The National Academies’ recommendations:

The National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine’s panel on sexual harassment of women in those fields made a number of recommendations to reduce harassment in the lab, which appear below. elaborates on specific actions to accomplish each recommendation.

- Create diverse, inclusive and respectful environments.

- Address the most common form of sexual harassment: gender harassment.

- Move beyond legal compliance to address culture and climate.

- Improve transparency and accountability.

- Diffuse the hierarchical and dependent relationship between trainees and faculty.

- Provide support for the target.

- Strive for strong and diverse leadership.

- Measure progress.

- Incentivize change.

- Encourage involvement of professional societies and other organizations.

- Initiate legislative action.

- Address the failures to meaingfully enforce prohibitions on sex discrimination.

- Increase federal agency action and collaboration.

- Conduct necessary research.

- Make the entire academic community responsible for reducing and preventing sexual harassment.

Institutional secrecy can be damaging

Universities guard the results of Title IX cases as . Although required by law to disclose violent crimes, including sex offenses that happen on or near their campuses, universities generally don’t release information about the prevalence of sexual harassment complaints, the perpetrators or how they are punished. Often, college officials make the argument that harassers should have an opportunity to learn from their mistakes. While the practice stems from due process and privacy concerns, it can obscure the number and nature of problems caused by serial harassers, allowing them to move from one institution to another or operate without oversight at meetings.

Molecular biology professor Jason Lieb resigned from the University of Chicago in 2016 after he made unwelcome sexual advances to numerous students at a departmental retreat and, according to some reports, raped a student incapacitated by alcohol. The assistant provost who oversaw the investigation recommended that Lieb be fired. He resigned before that could occur.

Before being hired at the University of Chicago, Lieb had been the subject of a Title IX investigation at the University of North Carolina. He was then recruited from UNC to Princeton for a director position, from which he abruptly resigned just seven months later. The that the hiring committee in Chicago had received an anonymous tip that both prior universities had launched Title IX investigations of Lieb. While the hiring committee reviewed the file from UNC, which found no policy violation, before making the decision to hire Lieb, neither the hiring committee nor the Times could obtain clarity about what happened at Princeton.

According to the National Academies report on sexual harassment, “Institutions gain protection from liability by adopting standard practices that perpetuate ineffective policies and shield patterns, perpetrators and outcomes from scrutiny.” One of the major recommendations in the report is that universities make their investigation and sanctioning procedures public and transparent to prevent cases like Lieb’s.

Title IX: It’s not just for students

The Civil Rights Act of 1964 included 11 sections; as written, Title IX refers to participation in federally funded educational programs, while a different clause, Title VII, applies to racial and gender discrimination in employment. So how did Julie Libarkin, a university employee, end up at her university’s Title IX office?

According to the U.S. Department of Education, Title IX applies to all areas of education. In a 2013 white paper, the Association of Title IX Administrators explained that this includes protecting faculty and staff from gender discrimination, harassment and assault.

“We’re not suggesting that Title VII doesn’t apply to an employee-on-employee complaint of sex or gender discrimination, ” the white paper states. “It does. But Title IX is an additional overlay, and colleges and universities must be compliant with both laws.”

Recent case law also has extended Title IX protections to trainees outside of university settings. In a key lawsuit, a former medical resident harassment by the training program director at her hospital and retaliation after she reported him — which culminated in her dismissal from the residency program — violated the hospital’s Title IX obligations. In the wake of a 2017 decision that Title IX applied to the dismissed resident, said Michelle Issadore of the Association of Title IX Administrators, health science centers and training hospitals have begun to set up Title IX processes.

“Their questions are really specific and unique compared to colleges and universities,” Issadore said. “It’s an area where we’re continuing to learn and grow.”

Broadening support for trainees

The National Academies of Science, Engineering and Medicine’s 2018 report on sexual harassment of women, released this summer, noted that concentration of authority in one adviser with make-or-break power over trainees’ careers puts the less powerful parties at risk of harassment or assault. One proposal to revamp the academic hierarchy is to expand a trainee’s team of formal mentors. Annual thesis committee meetings in several graduate programs around the U.S. require the student to speak to the committee without the primary adviser.

There is debate about whether this intervention truly will enable reporting. Scott Barolo, graduate director of the program in biomedical sciences at the University of Michigan, is among those who question its effectiveness.

“There still may be some students who feel unsafe talking to their committee, even with their adviser standing out in the hallway,” he said.

According to Jennifer Freyd, a psychology professor at the University of Oregon, the policy is still worthwhile.

“When you ask somebody who’s being mistreated about how it’s going, and you attend to their answer, no matter what their words are you can begin to pick up what’s really going on,” she said. “They hesitate a little. They look down at the floor. That doesn’t prove anything, but it’s a red flag that you need to follow up on.” Freyd said that just being aware of committee surveillance may rein in professors who take advantage of perceived opportunities to abuse their students.

Meanwhile, other approaches could broaden trainees’ support networks. This year, Barolo’s program is rolling out mentoring groups that will introduce first-year students to a range of senior students and faculty early on.

“In my experience, when students are in distress for any reason, sometimes they want to talk to a faculty member they know really well. Sometimes they want to talk to a faculty member who is outside their program,” Barolo said. “The best thing we can do is make sure there are opportunities for all those possible interactions to happen.”

Double jeopardy: The intersectionality of sexual harassment

While most women are sexually harassed at some point, some women are targeted disproportionately. The National Academies report on sexual harassment cited multiple studies showing that women who belong to ethnic or sexual minority communities face more harassment than white women.

A seminal article published in 2006 reported that women who are ethnic minorities are in “double jeopardy,” facing both sexual harassment and ethnic harassment at work. The same is true among scientists; confirmed that women from minority communities experienced more harassment and felt less safe in the lab than either their male counterparts or white women.

Not only are women from minority communities harassed more often, but the harassment also can be more damaging. This disproportionate impact is thought to come from more frequent, subtle messages that people with multiple marginalized identities don’t belong or are .

Sonia Flores

Sonia FloresSonia Flores, vice chair of diversity and justice and professor at the University of Colorado Denver and chair of the 91—«…´¥´√Ω’s Minority Affairs Committee, said she has noticed a change in workplace bullying over the past few years.

“Men are more conscientious about sexual harassment. But the discrimination based on ethnic background is even more pervasive,” Flores said. “Here at the hospital, we’ve seen an increase of maybe 25 percent.”

The increase, which began after the 2016 election, stems mostly from patients harassing doctors, nurses and medical trainees of color, she said.

In her role as vice chair of diversity and justice, Flores is developing a code of conduct for patients and a toolkit care providers can use in response to harassment from their patients. She also has started doing bystander training, which equips people to intervene on behalf of their colleagues.

“It’s important that people become allies, regardless of their ethnic background and gender,” Flores said.

A 2000 study on sexual harassment and racial disparity argued that women of color may be less likely to report their harassers than their white counterparts. According to Flores, this is because the risks associated with reporting a harasser are even higher for minority women.

“I think it’s not only the fear of retaliation, but the fear of being labeled a troublemaker,” she said, noting negative racial stereotypes tied to expressions of emotion.

And for a woman who experiences harassment, according to Jasmine Mena, a psychology professor at Bucknell University, it can be impossible to determine what dimension of her identity the harasser sees as a target. Many of these cases go unreported, making it difficult to gauge the prevalence of the problem.

While the available data suggest a troubling trend, many in the field agree that more research is needed.

Anita Hill famously spoke out in 1991 about her workplace sexual harassment by then-Supreme Court nominee Clarence Thomas, and she is now a professor of social policy, law, women’s, and gender and sexuality studies at Brandeis University. Hill joined a June discussion in Irvine, California, on the National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine report on the high prevalence of sexual harassment of women in science.

“There’s just not enough research around race and ethnicity and sexuality and harassment, and how it compounds,” Hill said. “How do we include more voices in this discourse that is under the radar?”

Changing federal Title IX requirements

Policy changes reportedly under consideration at the U.S. Department of Education, which were leaked to the New York Times in late August, would narrow institutions’ responsibility to redress sexual misconduct under Title IX.

While 2011 required universities to redress any conduct interfering with or limiting a student’s access to education, the leaked draft says Title IX covers only “unwelcome conduct … so severe, pervasive and objectively offensive that it denies a person access to the school’s educational program.”

According to the Times, the draft also restricts universities’ responsibility to include only misconduct that occurs on campus (not, for example, in the field or at a fraternity residence) and that is reported to a campus official. (Earlier guidance included any misconduct a university “knows, or reasonably should know, about.”)

The draft also includes procedural changes to Title IX investigations that would prioritize due process for the accused. This would align with sentiments expressed by U.S. Secretary of Education Betsy DeVos in 2017: “Every survivor of sexual misconduct must be taken seriously; every student accused of sexual misconduct must know that guilt is not predetermined.” Advocates for assault survivors and targets of harassment worry such changes would do further harm.

When this article went to press in late August, the Education Department had not released the full policy proposal. Needless to say, it may end up scrapped, revised or implemented.

Enjoy reading 91—«…´¥´√Ω Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreFeatured jobs

from the

Get the latest from 91—«…´¥´√Ω Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Policy

Policy highlights or most popular articles

91—«…´¥´√Ω honors Lawrence Tabak with public service award

He will deliver prerecorded remarks at the 2025 91—«…´¥´√Ω Annual Meeting in Chicago.

Summer internships in an unpredictable funding environment

With the National Institutes of Health and other institutions canceling summer programs, many students are left scrambling for alternatives. If your program has been canceled or delayed, consider applying for other opportunities or taking a course.

Black excellence in biotech: Shaping the future of an industry

This Black History Month, we highlight the impact of DEI initiatives, trailblazing scientists and industry leaders working to create a more inclusive and scientific community. Discover how you can be part of the movement.

91—«…´¥´√Ω releases statement on sustaining U.S. scientific leadership

The society encourages the executive and legislative branches of the U.S. government to continue their support of the nation’s leadership in science.

91—«…´¥´√Ω and advocacy: What we accomplished in 2024

PAAC members met with policymakers to advocate for basic scientific research, connected some fellow members with funding opportunities and trained others to advocate for science.

‘Our work is about science transforming people’s lives’

Ann West, chair of the 91—«…´¥´√Ω Public Affairs Advisory Committee, sits down Monica Bertagnolli, director of the National Institutes of Health.