JLR: A close-up of nascent HDL formation

Oil and water don’t mix. But our aqueous blood is full of hydrophobic lipids — including cholesterol. To travel via the bloodstream, those lipids must hitch a ride on an amphipathic carrier. in the Journal of Lipid Research, scientists at Boston University report an advance in our mechanistic understanding of how one such carrier forms.

“Lipoproteins are like boats that deliver and remove cargoes of fatty substances to and from our cells,” said , chair of the physiology and biophysics department at Boston University School of Medicine and senior author on the JLR paper.

The subset of those “boats” that carry cholesterol and other lipids to the liver from other parts of the body are called high-density lipoproteins, or HDL, aka “good cholesterol.” HDL can remove cholesterol from distal cells — such as macrophages in the walls of arteries, where cholesterol accumulation can lead to heart attacks — and deliver it to liver cells, a process known as reverse cholesterol transport. The liver disposes of excess cholesterol by converting it into bile acids secreted into the small intestine.

According to Atkinson, a biophysicist, most of what is known about HDL formation comes from experiments that take a cell biological tack. In such studies, he said, “You can see (HDL formation) happening, and you can quantitate what happens, but you don’t understand the driving interactions that cause it to happen.”

HDL is built on a scaffold protein, apolipoprotein A-I. This apoA-I is thought to collect cholesterol and phospholipids from the cell membrane. Atkinson’s team wanted to better understand that process.

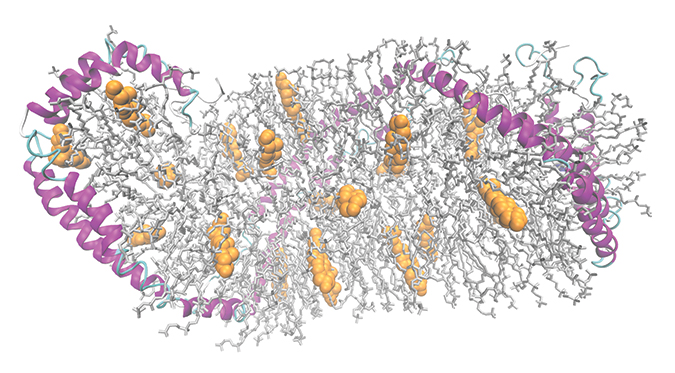

A model of a high-density lipoprotein particle shows apolipoprotein A-I in pink, phospholipids in gray and cholesterol in yellow.Wu et al/JBC 2009ApoA-I depends on a lipid transporter protein, ABCA1, that pumps cholesterol from the inner to the outer leaflet of the cell membrane. Because the cholesterol that ABCA1 transfers usually ends up bound to apoA-I, some researchers suspected a physical interaction between apoA-I and ABCA1. Others argued that cholesterol and phospholipids could diffuse passively and bind to apoA-I.

A model of a high-density lipoprotein particle shows apolipoprotein A-I in pink, phospholipids in gray and cholesterol in yellow.Wu et al/JBC 2009ApoA-I depends on a lipid transporter protein, ABCA1, that pumps cholesterol from the inner to the outer leaflet of the cell membrane. Because the cholesterol that ABCA1 transfers usually ends up bound to apoA-I, some researchers suspected a physical interaction between apoA-I and ABCA1. Others argued that cholesterol and phospholipids could diffuse passively and bind to apoA-I.

“Even if you demonstrate that apoA-I binds to the cell surface, you don’t actually know that it’s bound to ABCA1. It’s just bound to the cell surface,” Atkinson said. So he asked his team to see if they could “demonstrate that interaction actually happening in the isolated components.”

The team, led by graduate student Minjing Liu and supported by and , used isolated apoA-I and ABCA1 to test for a physical interaction. They were able to show immunoprecipitation of apoA-I with purified ABCA1.

The lab earlier had designed a mutant apoA-I with a little extra wiggle in an already flexible hinge region. For this study, they used the mutant to show that higher flexibility increased apoA-I lipidation, or the formation of nascent HDL. The team has not yet tested whether the extra-flexible mutant binds to ABCA1 better or whether binding of either form of apoA-I activates ABCA1.

But about one thing Atkinson is certain: “It’s the apoA-I/ABCA1 interaction which then enables the nascent HDL particle formation to happen as the membrane components are being transported out by ABCA1.”

Increasing reverse cholesterol transport may be a way to reduce atherosclerosis and heart disease. Atkinson is optimistic about the promise of understanding the physiological processes better.

“Translational research might be in vogue,” he said, “but remember that if you don’t do foundational basic discovery research, you will not have anything to translate.”

Enjoy reading 91—«…´¥´√Ω Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from 91—«…´¥´√Ω Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Gaze into the proteomics crystal ball

The 15th International Symposium on Proteomics in the Life Sciences symposium will be held August 17–21 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Bacterial enzyme catalyzes body odor compound formation

Researchers identify a skin-resident Staphylococcus hominis dipeptidase involved in creating sulfur-containing secretions. Read more about this recent Journal of Biological Chemistry paper.

Neurobiology of stress and substance use

MOSAIC scholar and proud Latino, Bryan Cruz of Scripps Research Institute studies the neurochemical origins of PTSD-related alcohol use using a multidisciplinary approach.

Pesticide disrupts neuronal potentiation

New research reveals how deltamethrin may disrupt brain development by altering the protein cargo of brain-derived extracellular vesicles. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics article.

A look into the rice glycoproteome

Researchers mapped posttranslational modifications in Oryza sativa, revealing hundreds of alterations tied to key plant processes. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics paper.

Proteomic variation in heart tissues

By tracking protein changes in stem cell–derived heart cells, researchers from Cedars-Sinai uncovered surprising diversity — including a potential new cell type — that could reshape how we study and treat heart disease.