JBC: How bacteria build efficient photosynthesis machines

Researchers facing a future world with a larger human population and more uncertain climate are looking to photosynthetic bacteria for engineering solutions to improve crop yields.

In the Journal of Biological Chemistry, a Canadian research team on how cyanobacteria finesse one of the most wasteful steps in photosynthesis. The study investigated the assembly of carboxysomes in which the bacteria concentrate carbon dioxide, boosting the efficiency of a critical enzyme called RuBisCO.

“Essentially everything we eat starts with RuBisCO,” said , a professor at the University of Guelph in Ontario and senior author on the paper.

The enzyme, which is made of 16 protein subunits, is essential for photosynthesis. Using energy captured from light, it incorporates carbon dioxide into organic molecules from which a plant then builds new sugar. Unfortunately, it’s not terribly efficient. Or, from Kimber’s point of view, “RuBisCO has a really thankless task.”

The enzyme evolved in an ancient world where carbon dioxide was common and oxygen was rare. As a result, it isn’t very picky in discriminating between the two gases. Now that the atmospheric tables have turned, RuBisCO often accidentally captures oxygen, generating a useless compound that the plant then has to recycle.

Cyanobacteria make few such mistakes, because bacteria collect their RuBisCO into dense bodies known as carboxysomes. The bacteria pump bicarbonate (simply hydrated CO2) into the cell; once it gets into the carboxysome, enzymes convert the bicarbonate into carbon dioxide. Because the carbon dioxide can’t escape through the protein shell surrounding the carboxysome, it builds up to high concentrations, helping RuBisCO avoid costly mistakes.

Kimber wants to understand the logic of carboxysomes’ organization. “They’re actually phenomenally intricate machines,” he said. “The cyanobacterium makes 11 or so normal-looking proteins, and these somehow organize themselves into this self-regulating mega-complex that can exceed the size of a small cell.”

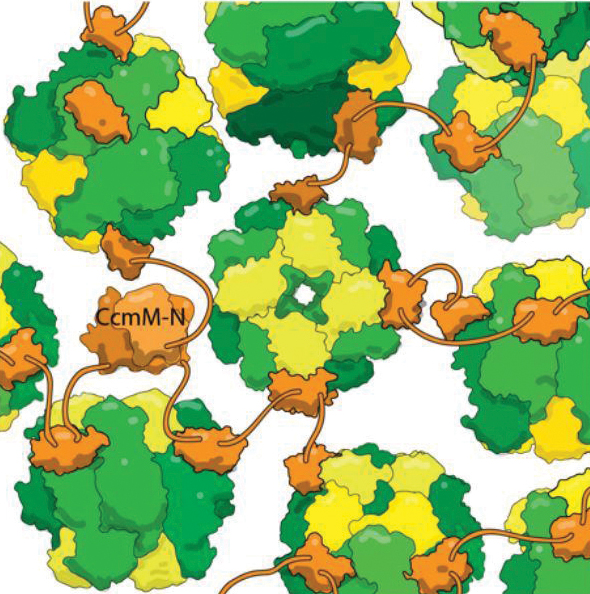

One of carboxysomes’ most impressive tricks is self-assembly, which Kimber’s lab set out to understand. They looked at a protein, CcmM, that corrals RuBisCO enzymes into new carboxysomes. They knew that part of CcmM looks a lot like a subunit of RuBisCO — so much so that researchers suspect ancient cyanobacteria created CcmM by duplicating a RuBisCO gene.

Most scientists in the field believed that CcmM binds to the enzyme by usurping that RuBisCO subunit’s spot. But when Kimber’s lab took a detailed look at CcmM’s structure and binding, the results showed that was wrong. True, CcmM was similar in shape to the small RuBisCO subunit. But the complexes it formed still included all eight small subunits, meaning that instead of stealing a spot from a RuBisCO subunit, CcmM had to be binding elsewhere.

“This is very odd from a biological perspective, because if CcmM arose by duplicating the small subunit, it almost certainly originally bound in the same way,” Kimber said. “At some point, it must have evolved to prefer a new binding site.”

The researchers also found that a linker between binding domains in CcmM is short enough that “instead of wrapping around RuBisCO, it tethers (individual enzymes) together like beads on a string,” Kimber said. “With several such linkers binding each RuBisCO at random, it crosslinks everything into this big glob; you wrap a shell around it, and this then becomes the carboxysome.”

last fall that they had succeeded in making tobacco plants with a stripped-down carboxysome in their chloroplasts. Those plants didn’t grow especially well, and the authors concluded that they had taken away too many components of the carboxysome; although it could be built in the chloroplast, it was a drag on the plants instead of a help.

A better understanding of how proteins like CcmM contribute to carboxysome construction and function could help bioengineers leverage carboxysome efficiency in the next generation of engineered plants.

Enjoy reading 91—«…´¥´√Ω Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from 91—«…´¥´√Ω Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Unraveling oncogenesis: What makes cancer tick?

Learn about the 91—«…´¥´√Ω 2025 symposium on oncogenic hubs: chromatin regulatory and transcriptional complexes in cancer.

Exploring lipid metabolism: A journey through time and innovation

Recent lipid metabolism research has unveiled critical insights into lipid‚Äìprotein interactions, offering potential therapeutic targets for metabolic and neurodegenerative diseases. Check out the latest in lipid science at the 91—«…´¥´√Ω annual meeting.

Melissa Moore to speak at 91—«…´¥´√Ω 2025

Richard Silverman and Melissa Moore are the featured speakers at the 91—«…´¥´√Ω annual meeting to be held April 12-15 in Chicago.

A new kind of stem cell is revolutionizing regenerative medicine

Induced pluripotent stem cells are paving the way for personalized treatments to diabetes, vision loss and more. However, scientists still face hurdles such as strict regulations, scalability, cell longevity and immune rejection.

Engineering the future with synthetic biology

Learn about the 91—«…´¥´√Ω 2025 symposium on synthetic biology, featuring applications to better human and environmental health.

Scientists find bacterial ‘Achilles’ heel’ to combat antibiotic resistance

Alejandro Vila, an 91—«…´¥´√Ω Breakthroughs speaker, discussed his work on metallo-Œ≤-lactamase enzymes and their dependence on zinc.