JLR: Spectroscopic studies scrutinize links between liver disease and mitochondria

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease, or NAFLD, is a metabolic disease that affects of American adults. Though the condition produces no noticeable symptoms, one out of every five patients will go on to develop a more serious condition called NASH (short for nonalcoholic steatohepatosis).

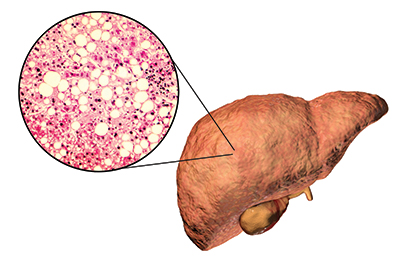

In fatty liver disease, hepatocytes fill with triglyceride vesicles. At this stage, the condition is reversible, but it can progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH, which involves irreversible tissue damage.

In fatty liver disease, hepatocytes fill with triglyceride vesicles. At this stage, the condition is reversible, but it can progress to nonalcoholic steatohepatitis, or NASH, which involves irreversible tissue damage.

The inflammation NASH causes can result in scarring, cancer and even organ failure. With those consequences in mind, researchers are working to understand the progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver to NASH.

It has been clear for some time that mitochondrial dysfunction has something to do with the onset and progression of nonalcoholic fatty liver. Two recent studies, described below, offer additional information on this front.

The first study illuminates how mitochondrial energy production stutters and fails as fatty liver disease progresses. The second study describes how changes to the liver in the course of disease affect the organ’s use of incoming nutrients.

Overworked cells

Kang-Yu Peng and a team of researchers from Australia and the Netherlands used lipidomics to analyze liver biopsies from obese patients with normal livers, fatty liver disease and full-blown NASH. was published in the Journal of Lipid Research.

Some of the changes the research team observed were predictable. For example, they saw an increase in triglycerides and an increase in acylcarnitine, a molecule that shuttles fatty acids to liver mitochondria so that the organelles can use the lipids in cellular respiration, in the patients with fatty liver disease and NASH. But the team also found significant changes in several lipid types without known connections to fatty liver.

They zeroed in on two lipids that participate in mitochondrial respiration: cardiolipin and ubiquinone. The researchers found that both lipids are elevated in the early stages of fatty liver and stay high as the disease progresses. The researchers think the level of both lipids, which are involved in the electron transport chain, may increase because mitochondria are working harder to deal with the excess energy.

This finding seems to support the notion that higher mitochondrial respiration compensates for having more triglycerides early in fatty liver disease. However, because of the increase in reactive oxygen byproducts, raising mitochondrial respiration also can be risky. For example, cardiolipin is highly susceptible to a chemical reaction called peroxidation, which can cause mitochondrial dysfunction.

The study also reported that the fatty liver biopsies had higher than normal accumulation of phosphatidylcholine and several types of ceramide. The significance of these changes isn’t yet clear.

More detailed study will be needed to determine whether, as the authors hypothesize, mitochondrial overwork contributes causally to mitochondrial failure and liver disease progression.

Building lipids, not glucose

One of the liver’s most important roles is to regulate the level of glucose in the blood, supplying energy to other tissues. When glucose is low, liver cells make more available by breaking down glycogen or converting other molecules to glucose. When glucose is plentiful, cells in the liver convert the sugar to other types of molecules or break it down and store the energy as ATP.

In in the Journal of Lipid Research, and colleagues at the University of Texas Southwestern Medical Center studied hepatocyte metabolism in obese individuals with normal or fatty livers.

The researchers used isotopically labeled glycerol, a versatile precursor of many organic molecules that can be made by breaking down glucose, to track metabolism. After a person absorbs a quantity of glycerol while fasting, their liver cells have a choice to make about the resource. Do they convert the molecule into a quick hit of glucose for energy; use it for longer-term energy storage as a triglyceride, which can be broken back down into glycerol later; or build nucleotides and amino acids? By analyzing patients’ plasma over time, the researchers could track how cells used the labeled molecules.

Patients with fatty livers tended to use glycerol to generate triglycerides more quickly than patients with normal livers and were slower to use it for making new glucose. There was no difference between groups in the pentose phosphate pathway that contributes to building other types of molecules.

The authors compared the liver cells’ preference for making more triglycerides, rather than using a new energy source right away, to a phenomenon observed in diabetic patients called metabolic inflexibility. That is, the fatty liver cells were slower to change from using stored carbohydrates to making new carbohydrates than the healthy liver cells. How the changes in metabolism of an incoming energy source may affect the progression of the disease remains to be seen.

Enjoy reading 91��ɫ��ý Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from 91��ɫ��ý Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Cracking cancer’s code through functional connections

A machine learning–derived protein cofunction network is transforming how scientists understand and uncover relationships between proteins in cancer.

Gaze into the proteomics crystal ball

The 15th International Symposium on Proteomics in the Life Sciences symposium will be held August 17–21 in Cambridge, Massachusetts.

Bacterial enzyme catalyzes body odor compound formation

Researchers identify a skin-resident Staphylococcus hominis dipeptidase involved in creating sulfur-containing secretions. Read more about this recent Journal of Biological Chemistry paper.

Neurobiology of stress and substance use

MOSAIC scholar and proud Latino, Bryan Cruz of Scripps Research Institute studies the neurochemical origins of PTSD-related alcohol use using a multidisciplinary approach.

Pesticide disrupts neuronal potentiation

New research reveals how deltamethrin may disrupt brain development by altering the protein cargo of brain-derived extracellular vesicles. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics article.

A look into the rice glycoproteome

Researchers mapped posttranslational modifications in Oryza sativa, revealing hundreds of alterations tied to key plant processes. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics paper.