JBC: What happens to plasmalogens, the phospholipids nobody likes to think about

Alzheimer’s disease patients lose up to 60 percent of a component called plasmalogen from the membranes of the cells in their brains, but we don’t know how or why. In in the Journal of Biological Chemistry, researchers at Washington University in St. Louis provide the first report of an enzyme that breaks down plasmalogens, a breakthrough in understanding the molecular processes that occur during Alzheimer’s and other diseases.

Plasmalogens are particularly abundant in the heart and brain, where they are involved in structuring cell membranes and mediating signals. Plasmalogens are phospholipids defined by a particular chemical bond called a vinyl-ether linkage. Due to the technical difficulties of studying plasmalogens, however, many aspects of their biology are unknown, including how the vinyl-ether bond is broken to break down plasmalogens in cells.

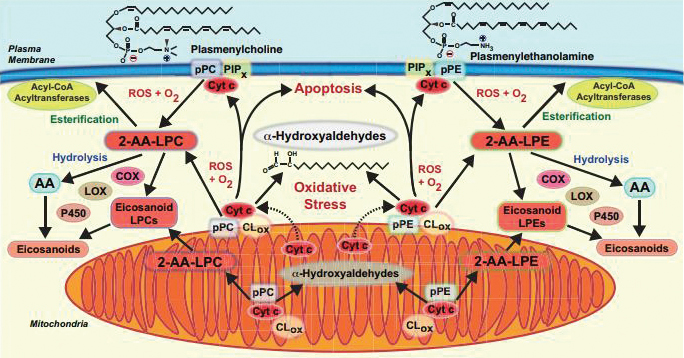

This diagram shows signaling pathways affected by cytochrome c’s degradation of plasmalogen. Courtesy of Richard Gross is the researcher at Washington University who oversaw the new study. “These molecules, plasmalogens, have been swept under the rug because nobody likes to think about them,” Gross said. “(They’re) hard to work with. They’re susceptible to light, they’re stable in only certain solvents, they have a limited lifespan after they’re synthesized unless extreme precautions are taken, and they’re expensive to make and synthesize.”

This diagram shows signaling pathways affected by cytochrome c’s degradation of plasmalogen. Courtesy of Richard Gross is the researcher at Washington University who oversaw the new study. “These molecules, plasmalogens, have been swept under the rug because nobody likes to think about them,” Gross said. “(They’re) hard to work with. They’re susceptible to light, they’re stable in only certain solvents, they have a limited lifespan after they’re synthesized unless extreme precautions are taken, and they’re expensive to make and synthesize.”

In the new study, Gross’ team performed painstaking experiments to find the elusive mechanism by which plasmalogens are enzymatically degraded. Cytochrome c is a protein typically found in mitochondria, where it facilitates electron transport. It can be released into the cell under stressful conditions.

Gross’ team showed that cytochrome c released from the mitochondria can acquire a new function: acting as a peroxidase to catalyze the breakdown of plasmalogens in the cell. Further, the products of this reaction are two different lipid signaling molecules that previously were not known to originate from plasmalogen breakdown.

“That was one thing that surprised us,” Gross said of the signaling products. He said he also was surprised by the ease with which the bond is broken. “The implication is that there is probably a lot of plasmalogen (breakdown) that’s going on in conditions of oxidative stress.”

The results tie in with another observation about the brain cells of Alzheimer’s disease patients, which is that they often have dysfunctional mitochondria and a resultant release of cytochrome c.

Gross is interested in delving deeper into how and why plasmalogen loss occurs in Alzheimer’s patients, particularly those who develop the disease in old age, not due to familial mutations. Gross speculates that as people age, the accumulation of reactive oxygen species leads to cytochrome c release, activation of its peroxidase activity and plasmalogen breakdown in many membranes.

The results also have implications for understanding disorders in the heart and other plasmalogen-rich tissues, integrating studies of mitochondria, cell membranes and cell signaling under stressful conditions.

“This is like a quantum jump into the future,” Gross said.

Enjoy reading 91—«…´¥´√Ω Today?

Become a member to receive the print edition four times a year and the digital edition monthly.

Learn moreGet the latest from 91—«…´¥´√Ω Today

Enter your email address, and we’ll send you a weekly email with recent articles, interviews and more.

Latest in Science

Science highlights or most popular articles

Bacterial enzyme catalyzes body odor compound formation

Researchers identify a skin-resident Staphylococcus hominis dipeptidase involved in creating sulfur-containing secretions. Read more about this recent Journal of Biological Chemistry paper.

Neurobiology of stress and substance use

MOSAIC scholar and proud Latino, Bryan Cruz of Scripps Research Institute studies the neurochemical origins of PTSD-related alcohol use using a multidisciplinary approach.

Pesticide disrupts neuronal potentiation

New research reveals how deltamethrin may disrupt brain development by altering the protein cargo of brain-derived extracellular vesicles. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics article.

A look into the rice glycoproteome

Researchers mapped posttranslational modifications in Oryza sativa, revealing hundreds of alterations tied to key plant processes. Read more about this recent Molecular & Cellular Proteomics paper.

Proteomic variation in heart tissues

By tracking protein changes in stem cell–derived heart cells, researchers from Cedars-Sinai uncovered surprising diversity — including a potential new cell type — that could reshape how we study and treat heart disease.

Parsing plant pigment pathways

Erich Grotewold of Michigan State University, an 91—«…´¥´√Ω Breakthroughs speaker, discusses his work on the genetic regulation of flavonoid biosynthesis.

.jpg?lang=en-US&width=300&height=300&ext=.jpg)